We’re all sat in the front room, practically eating our lunches off mouse mats – the computers and keyboards take up most of the available desk space.

Carl is closest to the front door and jumps up each time there’s a knock. “We’re open again at half past,” he repeats politely, “we’re just getting ourselves something to eat. Are you all right to come back in half an hour? Great, see you later.”

Between mouthfuls of pasta from a plastic tub, Vanessa, the UCAN manager, tells me that the afternoon is set aside for an IT class. “It’s very relaxed,” she says. “We’ve discovered that a drop-in works better than a formal course. Customers don’t have to stay for the whole session – which can feel daunting – but most of them do.”

“If people can get to know how the computer works then they are more likely to access services online. If we are being posh, we’d call it digital inclusion.

“Last year the government changed the way jobseekers look for work. All new jobseekers now have to set up a government online account – which is challenging enough – and then upload a CV before they can start looking for a new job.

“The theory is great if you are IT savvy,” she says. “But when you mention uploading a CV to some of our customers you might as well be talking a different language.”

“So, if someone finds themselves out of work,” I say, “it could be several weeks before they are able to learn the necessary IT skills to apply for another job?”

“Yes, some have never touched a keyboard before,” says Vanessa, “and it was bedlam in here when it was first introduced. People were dead nervous.

“The CV is now the Willy Wonka golden ticket,” she says. “Gone are the noticeboards in the Jobcentre, all the available vacancies are now online on what’s called the Universal Jobmatch. And the Jobcentre can now check whether you’re actively searching for a job and impose sanctions if you’re not.”

As plates and mugs find their way back to the kitchen sink, freelance IT tutor Charlotte, arrives and within minutes four participants follow and settle themselves in front of a screen. I explain to Charlotte and her class about this blog, “I’d like to take some pictures if that’s okay with everyone, and maybe ask a few questions.”

“Paul is one of our star pupils,” says Charlotte, pointing out an older man who has already logged on. So I start with Paul.

“Seven months ago I was made redundant from my job as a driver,” he says. “For ten years the only computer I’d used was the sat nav! I didn’t even know how to switch one on.”

After coming to a few Monday afternoon sessions Paul says he found his way round the PC. “It’s no problem now. I’m starting a new job tomorrow and they asked if I could use a computer and I said I could. So I’ll be doing some forklift truck driving and keying in goods in and goods out, that sort of thing. They’ll show me what to do, won’t they?”

“I’m sure they’ll give you some training before they let you loose,” I say. “Do you mind me asking, how old are you Paul?”

“61.”

Another older man comes in as I’m talking to Paul and I overhear him tell Charlotte that he needs some help uploading his CV onto the Universal Jobmatch site. “That’s fine,” she says, “and it’s something I can help you with but I try and start everyone off with a little online course about finding their way around the keyboard. Are you okay if I set you off with that first?”

I haven’t taken my coat off and Vanessa has already introduced me to Cath, a freelance employment advisor.

“What do you do at the UCAN?” I ask her as a mug of tea is pushed into my hand.

“Whatever people need to do with employment and training,” she says. “If we hear that ten people are looking to get a store job in the run-up to Christmas then I’ll put on a little course on applying for retail jobs. That sort of thing.”

This UCAN prides itself on its responsive approach. Why offer apples when people want oranges, I had been told. There’s no point delivering services that no one needs.

Today is day three of a four-day course Cath is running to boost self-esteem and motivation. Before she can explain the ins and outs we’re interrupted by a knock on the door. The centre isn’t officially open for another 15 minutes.

“Can I use the phone?” asks a middle-aged man. “Vanessa said I could come early. I need to call them about my tax credits and make sure they’ve got my new address.”

Cath lets the man in and as soon as she sits down again there’s another knock on the door. It seems we’re not going to manage even the briefest of conversations. “I’ll pop up to your course later,” I say, “if that’s okay.”

Today it’s going to be busy. It’s money day and both Dawn from Money Skills and Steve from the Hoot credit union are in. And so is Jade from Think Positive, an ‘emotional wellbeing’ service. Vanessa introduces me to them all as the UCAN Centre starts to fill up with customers.

I’m feeling a little overwhelmed by it all and I take my tape recorder and camera and take refuge in Cath’s course in the upstairs meeting room.

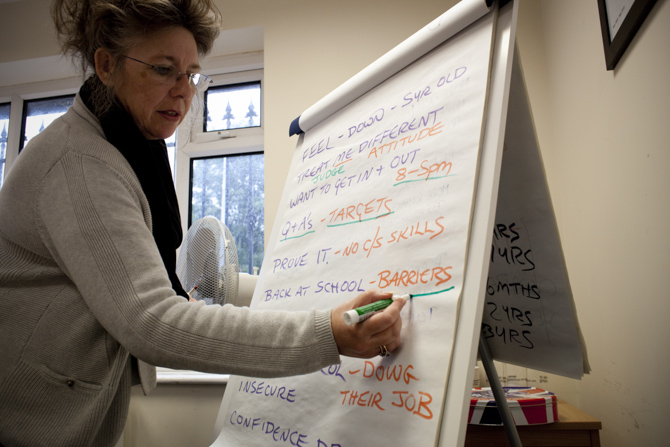

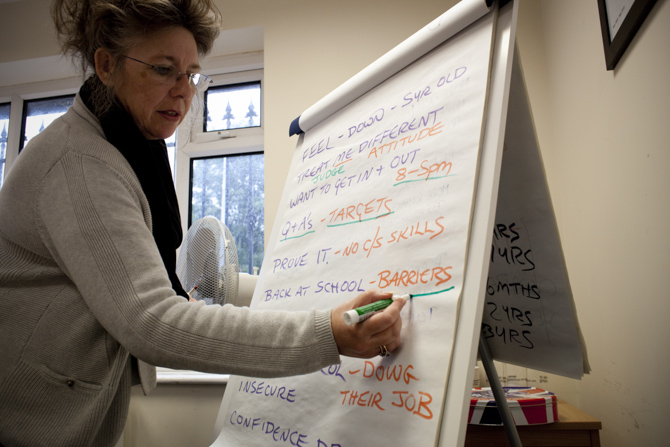

Two men and four women are sitting round a table strewn with sweets and biscuits. Cath is asking about their perceptions of the Jobcentre. “You say it’s depressing as soon as you walk in, but what, specifically do they do to you?

She is bombarded with negatives about people’s Jobcentre experiences and, pulling the top off a marker pen, has trouble writing them on her flip chart fast enough. “It’s horrible, I hate it… They ask you lots of questions: What jobs have you been looking for? Can you prove it?… It makes you feel like you’re back at school… You feel belittled…”

“As soon as you walk in that door your confidence just goes,” says one of the women. “You feel insecure.”

“You feel insecure, Morag? Isn’t it amazing how powerful this Jobcentre is? Look what it does to us,” says Cath, looking up from the flip chart.

“So let’s put ourselves in their shoes. We’re a Jobcentre advisor now. Do you think everyone walking towards their desk will have a gorgeous smile on their face?”

The participants, having enjoyed sharing what they hate about the JobCentre, are a little taken aback at having to see the situation from the other side. Everyone’s quiet as they try to imagine the scenario from the opposite angle. Cath suggests that the advisors will have targets and be under pressure to meet those targets.

“They still don’t have to talk to people the way they do,” says Morag. “They could talk to people nicely.”

“They must be like us though,” says a woman in a red top. “They must have good days and bad days.”

“What happens, do you think, when they leave the Jobcentre at the end of the day?” asks Cath.

“They forget about us,” says Morag.

“How do you know that?”

“I don’t. But that’s what I would do. I wouldn’t want to go home with my work.”

“But they’re not put in a cupboard to be recharged for the next day, are they?”

“They probably have pressures of their own,” says the woman in red, as the penny starts to drop.

“They are human beings like we are and they’ll have the same pressures: our bills, our debts, kids in trouble. Just because they are Jobcentre advisors doesn’t mean they’re not living every day like we are. And then they’ve got the likes of Mr Cameron telling them they’ve each got to get, say, 120 people into a job this month.”

“When there aren’t any,” someone says.

“When there aren’t any,” repeats Cath. “So, do you think they feel pressure? Of course they do. Even before they open the door to you guys.”

“And then we knock on the door,” laughs one of the men.

“Do you think they feel insecure? Is there a chance on it?” continues Cath. “With all that they have going on, do you think there’s a chance some of them might feel insecure?”

There are reluctant nods from around the room.

“So, what do you think would help your next visit to the Jobcentre? What could you do?”

“Smile,” someone says quietly as if breaking ranks.

“Walk towards them smiling,” repeats Cath.

Ten minutes ago it would have been like throwing a hand grenade into the room if someone had suggested smiling at a JobCentre advisor but Cath has got them there – most of them anyway – and now the group realise that it’s their own attitude that affects the outcome of their Jobcentre experience.

“Won’t it get me into trouble though?” asks Morag.

“When was the last time anyone was imprisoned for smiling?” suggests Cath, with a big grin. “If you understand a bit more about them and have more self awareness about yourself then you can actually help to change their approach towards you.

“It’s about making it a win-win situation for you. And please don’t think the Jobcentre advisors are out to get you. They’re not. Change that perception. They have their limitations like we all do.

“And don’t expect them to do everything for you, because they can’t. Remember the UCAN has got experts to help you with a CV… we want you to have the best.”

Yesterday, at his party’s conference, the chancellor George Osbourne announced plans for a Help to Work scheme for the long-term unemployed. This morning’s free paper has already dubbed it ‘Womble for welfare’ as it’d require claimants to pick up litter and clean graffiti.

I thought Cath – the employment advisor whose course I wrote about – would be dead against it. “If it helps build up self-esteem and motivation I’d be right behind it,” she says. “But, you know, they’ve had these ideas before and mostly it’s to please the voters, they are never planned out properly.

“I guarantee if we interview every single person who is unemployed there would be very few who say they love it. Very few. But the fear of losing their benefits is immense and so they’d rather stay where they are, it feels safer. When a new scheme sounds like a threat – like this does – then it’s not going to work.”

It’s employment day at the UCAN and the regular staff have some specialist support. As well as Cath, there’s Michael, locally-renowned for his CV expertise; Paula, a training provider, who plugs her BTEC courses and Nigel from the Careers Service who barely has space in one of the small offices to perch his laptop.

By mid morning Morag has arrived. She’s excited about having an application form to fill out. A friend told her about a cleaning job at the town’s theatre and she’s clutching the job spec and application form. She has until five tomorrow to return the completed form.

“The important part is this,” says Carl as he shows her the ‘essential criteria’ part of the job spec. “Here you might want to demonstrate how you’ve worked as part of a team. For example, while I was working for such and such a company, I worked as part of a team…”

“…can that be for a school as well? When we were doing displays we all used to work together.”

“Yeah, that’s great. Anything like that,” says Carl. “Clean to high standards, to be punctual and efficient, able to be flexible as regards working hours. So you need to think how you meet these. They are the skills you need to do this job, that’s basically what they are saying.”

There seems to be a change in Morag even since last week when we went to the Jobcentre together. Since then she’s been to a job fair; she’s getting help with an application and is coming back this afternoon to see Nigel, the careers advisor.

Within ten minutes of the work club session starting after lunch, all the computers are occupied. Notebook in hand, I look around the small room, trying to work out who’s doing what.

CV maestro Michael is helping a man complete his CV for a warehousing job. Next to him Paula is helping another. Rosanne is keeping tabs on who is next in the queue for either a CV or a consultation with Nigel.

The front door is opened again and again. Each time a head bobs in, takes a look at the frenetic activity and disappears. “I’ll be back later,” I hear one of the heads say.

Carl is multi-tasking, trying to help three people at once. “Just give me five minutes,” he says to one, as he jumps to another, “I’ll be right with you.”

There are now 18 people in the room. It would make a good photograph but, when I suggest it, not everyone is keen. I make do with the back of some heads.

Morag has finished her consultation with Nigel. “How did that go?” I ask, as she heads for the door.

“Great,” she says, “he’s given me some good ideas.”

“You really seem to be enjoying looking for work,” I say.

“I am. I’m determined to get a job.”

This was the morning after the first episode of Benefits Street, the now controversial Channel Four documentary following benefit claimants on a single Birmingham street.

“Not one of them, I believe, want to get a job,” says Darren as we sit in the upstairs office. “It was just drink and drugs… skipping through life… it’s not typical of what it’s like on benefits. It’s probably one of the worst streets in Birmingham, but that’s not the point, no matter where you live you can try and find a job.

“No one on that programme were determined enough. They were getting out of bed and it was fag in mouth and can in hand. You just can’t do that.”

Darren is 37 but looks 25. Four years ago he had an operation on his feet and spent the next 18 months in a wheelchair. This month he’s just received the first pay packet he’s had for two years. He’s a UCAN success story and he doesn’t mind who knows.

“When I was out of work I’d get into a routine: every morning I’d come down to the UCAN. It’d get me out of the house, stop me looking at the four walls or watching TV. If you want a job, you have to have the right mindset.

“But that operation took me out for a long time. My self-esteem took a big knock. When someone sits you down and says, ‘It’s going to be difficult for you Darren, you’re going to have to learn to walk again’, then your confidence goes.”

“But you did do it,” I say, “you did learn to walk again.”

“Yeah. Yeah. I’ve done it. I still struggle a bit but if someone saw me on the street I’d just look like anyone else.”

Once recovered Darren got work through an agency as a warehouse order picker which he did for two years. He was then on benefits for a fortnight before he got another job doing the same kind of work. Five months later he was laid off. That was more than two years ago and it was then that he first started to use the UCAN.

“It’s been a tough time. Really tough. I wouldn’t want to do it again but you don’t have a choice, do you? At first I came to the UCAN every other day, then every day. I was unsure, shy really, and they helped me. I told them I wasn’t great on the computer and they put me on the IT course.

“I only had a paper CV – nothing I could email – and they helped me make a proper CV. Now I’ve got different CVs for different jobs and they’re absolutely immaculate, you’re not going to beat them.”

When Darren wasn’t spending time on the Work Programme – a compulsory ‘job club’ for the long term unemployed – he was at the UCAN sending off CVs. “Me, personally, I would be applying for 10 jobs a day. That’s me. That’s my preference.”

“Why? What makes you so motivated?” Daft question.

“Because I want a job. I believe, in my head, if you are determined enough, there’s something out there for everyone.”

“Are there enough jobs for people who want them, do you think?

“It depends what sort of job you want,” he says. “I believe if you aim too high you’ll only be disappointed. You have to be realistic. Believe me, I don’t want national minimum wage but you have to go for it. Anything else is a bonus. You can work your way up.”

Darren has now a job on the help desk of some security company. He receives calls when building alarms are triggered and sends an engineer to investigate. With his first wages he wandered into Currys and bought himself a washing machine.

As we’re talking I imagine what sort of TV programme the documentary team might have made had they followed Darren for the last twelve months. It wouldn’t be very exciting, and certainly wouldn’t make prime time.

There’d be hours of footage of Darren in front of the computer looking for work; shots of him cooking his own fresh food – “I’d rather make something myself than get a takeaway” – and not a single scene of drunken excess because, as he says, “for me, paying the bills is more important than drinking”.

If Benefits Street isn’t typical then maybe super-motivated, healthy-eating Darren isn’t either but there must be plenty of people in between.